#IdleNoMore

What was #IdleNoMore ?

The #IdleNoMore movement was founded by four women: Nina Wilson a Nakota and Plains Cree from Treaty 4 White Bear, Sylvia McAdam a Cree from Treaty 6 territory, and Jessica Gordon, Pasqua 4 Treaty Territory and Sheelah McLean, a non-Indigenous woman from Saskatchewan.

In the Fall of 2012 they became concerned about proposed federal legislation, specifically a 457-page omnibus bill, officially known as the Jobs and Growth Act, but commonly called Bill-C-45. The bill aimed to alter 74 pieces of existing legislation so that fewer environmental assessments were required of industry, pipelines would be exempted from the navigable waters act, and only fish of commercial importance would be protected under environmental regulations. It also made changes to the Indian Act, so that land could be more easily surrendered for commercial development. In short, it the bill reduced environmental regulations to make way for industry, particularity oil and gas pipelines.

The #IdlenoMore (#IDNM) founders, believed the Harper government had purposely designed C-45 to be long, complex, and difficult to communicate to public. They were not alone. Opposition parties and the media had similar criticisms. Prime Minister Stephen Harper, and his conservative government held a majority at the time, meaning the Bill could pass even if very member of the opposition parties voted against it. Only public pressure on the Conservative party itself could stop the Bill.

“We were discovering things that were very concerning to us. Things that are hard to understand, very bulky. Very dense. I got a headache actually reading that Bill,” Nina Wilson said.

“Without land we’re not a nation. Without land we have no culture,” Sylvia McAdam explained.

How did IDNM’s understand its own success as a community?

On its “official” website which posted and tracked events and news in 2012-2013 #IDNM stated its vision. It was to be a peaceful movement, it was concerned with ensuring Indigenous people sovereignty to protect land and water was recognized.

If #IDNM’s goals could be summarized, into a list, it might look like this:

- Stopping Bill C-45 and creating a large and peaceful ‘revolution’ that would recognize Indigenous sovereignty.

- Communicate discontent with Canada’s environmental policies, and Indigenous authority to protect land and water

- Raising consciousness among Indigenous people

- ‘Flexing’

While #IDNM did not have achieve all of its goals, it was successful in organizing a real life social movement through social media.

Stopping Bill C-45 and creating a large and peaceful ‘revolution’ that would recognize Indigenous sovereignty.

The four founders began holding “teach-ins” on Nov 10. They set up a Facebook page to communicate and stream the teach-ins. Jessica Gordon says she needed to put in a name and typed in Idle No More “Because I’m not sitting here anymore… I’m not waiting.”

Bill C-45 was a spark, and immediate issue, which Indigenous people could rally around. However, underlying the Bill was the long-standing issue of consultation and consent when development is planned on Indigenous lands. In Canada large swatches of lands are protected by Treaties, other lands were never lost or surrendered. Canadian courts have occasionally blocked development when either industry or government has failed to consult Indigenous people and take their concerns to account. Courts have fallen short of Indigenous laws, which give Indigenous peoples a veto over development. Bill C-45 was understood to be an erosion of rights.

Among the early joiners of #IDNM were the Indigenous intelligentsia, those schooled in both Indigenous teachings by their communities and western knowledge through universities. among them Hayden King Anishinaabe from Beausoleil First Nation. he acknowledges underlying the legislation was a long-standing frustration with the Harper Conservatives, who had been in government since 2006, with a majority government since 2008.

“It was a decade of bad relationships with government. There was a mood,” he said.

Education about Bill C-45 remained a feature of the movement and social media was seen as a key to explain the threats to sovereignty and the environment of particular concern to Indigenous people, which was not being covered by media. So, for example on December 2, there was also a teach -in held on the blood reserve by four Indigenous female lawyers, streamed live on Youtube.

Although social media was originally seen as a tool for education, it soon became a tool for mobilization, according to journalist Rick Harp who followed the movement closely.

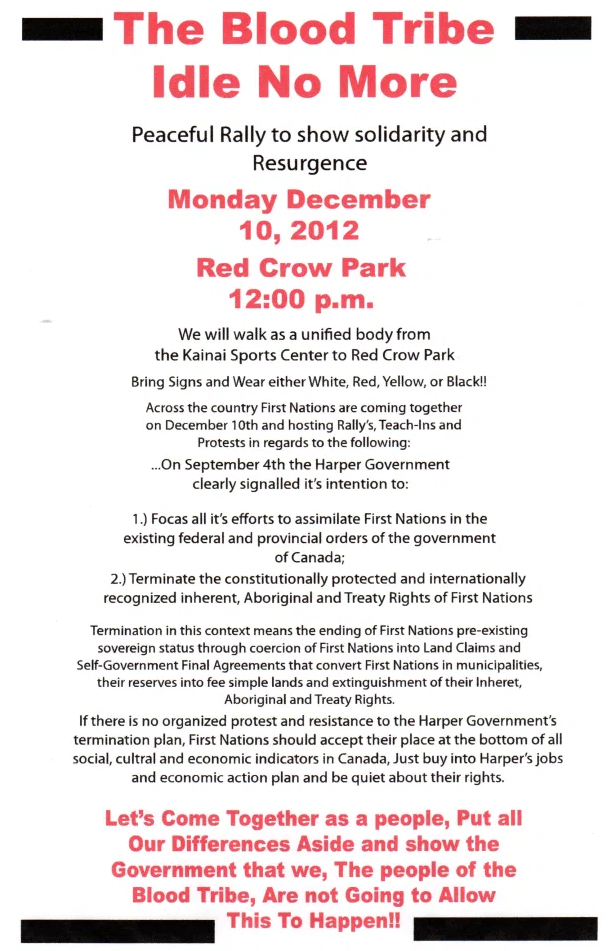

In Winnipeg, Wilson had tried previously to organize a rally about Bill-45 by door-knocking in Winnipeg. For the first one only a dozen people turned out. By December 10, buzz about #IDNM on social increased the interest and about 200 people came for a rally in the espite the cold Canadian winter.

“I’m really happy. I’m really proud of our people. I was overwhelmed earlier because just to see that many people coming together for something we all want, and want to work through. It was overwhelming and it was awesome,” Wilson later told APTN news.

Until December 4, the movement had been almost entirely organized by grassroots people. But that day a half dozen Chiefs who were in a meeting in Ottawa attempting to push their way into House of Commons, carrying a wampum belt.

Then on December 11, Chief Theresa Spence of the Attawapiskat First Nation in northern Ontario, set up a camp on Victoria island, in Ottawa a stone’s throw from Parliament hill, and began a hunger strike. Her demands to end the strike included a meeting between chiefs, and the Prime Minister and governor general.

The movement outlasted Bill C-45 which was passed without amendments on December 14, by the Conservative government who held a majority int the House of Commons. Instead of stopping, #IDNM grew.

Over the next weeks dozens of #IDNM rallies, marches and round dance flash mobs took place across Canada bringing out hundreds of people.

Unlike other Indigenous protests that tend to take place remotely, in one location on the site of development, these protests were urban, occurred quickly and seemingly randomly.

Little of this ensuing activity was coordinated by the four founders. IdleNoMore had no leader. It was a grassroots movement where any single person could spark a large action with a tweet or a Facebook post. It stunned government and became an issue of concern for the RCMP, even though they never became violent.

Typically, word of a planned event would be posted and spread on Facebook a day or two in advance, and spread through existing social networks. It would be amplifies on Twitter. The people now operating official and non-official #IDNM websites, Twitter, and Facebook accounts aggregated and amplified the posts.

According to the Globe and Mail the hashtag #IdleNoMore grew and would receive more than 144,000 tweets over Christmas Holidays (Dec 24-31) and 12,000 Facebook mentions.

December also started to see road blocks and disruptions to trains. There is no complete record of events, but a sampling from news coverage includes:

- Four highway blockades in Alberta included: Hobbema, Driftpile, Blood Tribe territory and Frog Lake First Nation.

- A blockade of the Trans-Canada Highway, Portage La Prairie, Manitoba

- Three Ontario blockades included: a shutdown of Highway 401 near London, a block of Highway 6 north of Manitoulin Island and a blockade of a rail line at a chemical factory near Sarnia.

- In Quebec highway 132 was shut down and a slowdown took place at Pointe-À-La-Croix, Quebec.

- A traffic slowdown took place at Campbellton, New Brunswick

- Two traffic slow-downs took place in Nova Scotia, with land protectors handing out information on Bill C-45

The founders were less sure about the road blocks.

“Excited and scared at the same time,” is how Nina Wilson described her feelings. “I worry for my people, I don’t want them to be incarcerated, I don’t want them to be in trouble, their kids left at home because they have to be in jail or in court. My mind was racing crazy.”

However no one controlled the movement. The founders had no authority, nor had they asked for any. While the movement was pan-Indigenous in the sense that it crossed all nations, each nation has its own organizing structure and grassroots connections. These took over the movement, spreading it, and giving local people the power to shape their actions as they wished.

Members of the #IdleNomore movement say the absence of an appointed leader or rule by committee was a more traditional form of Indigenous community organizing.

“In some ways I think that Idle No more reflected Indigenous notions of governance becaue there was no vocal individual you could go to” says Hayden King.

“From an Indigenous perspective it wasn’t leaderless; it is never leaderless. it was that power and leadership were dispersed and were being shared by a lot of people, ” says Tara Williamson a writer and educator who was part of the movement.

The messaging about dissatisfaction with federal laws governing the environment without consultation remained consistent. A key message was that Indigenous peoples have rights to govern traditional and unceded lands, whether by treaty, constitution or traditional law pre-dating Canada.

“Our community was already feeling a sense of angst, maybe, a sense of frustration,” says Tanya Kappo. She believes the atmosphere was ripe for an expression of discontent.

Social media spread word of the movement beyond Canada’s borders so that sympathy protests were held by Indigenous peoples in the US, Australia, New Zealand and other countries.

A large protest took place in Ottawa on January 11, 2013. Subsequently then Prime Minister Harper agreed to meet with Chiefs.

Prime Minister Harper agreed to meet with Chiefs. Only some of the chiefs agreed to meet, as the governor general was not present. Others did not feel a meeting with the Prime Minister was the point of the movement.

Chief Spence ended her hunger strike January 24, 2013.

The movement fizzled after January 2013, but didn’t disappear. The round dances had stopped but teach-ins continued. Social media connections had been made.

Subsequently conversations among Indigenous people questioned if the movement had accomplished anything.

Communicate discontent with Canada’s environmental policies, and Indigenous authority to protect land and water

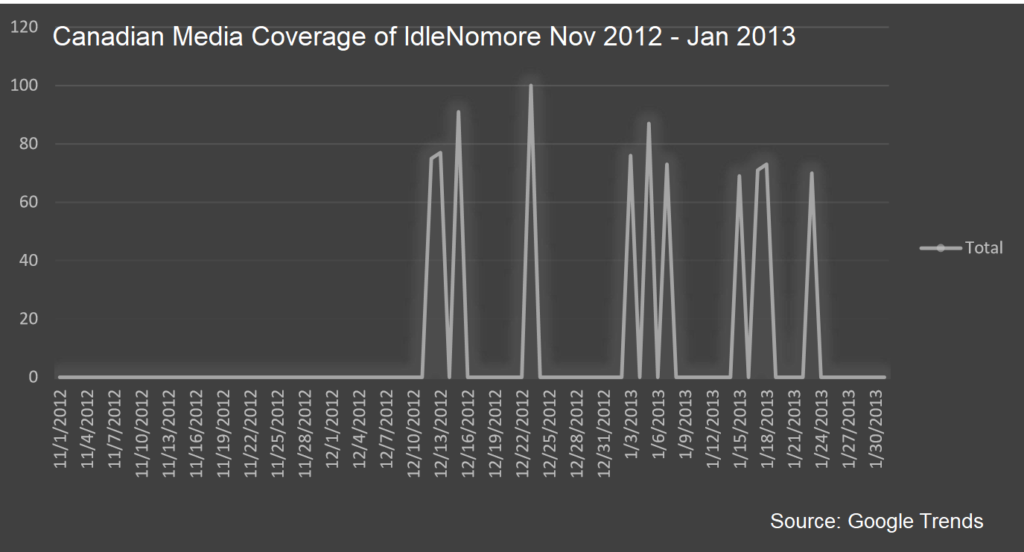

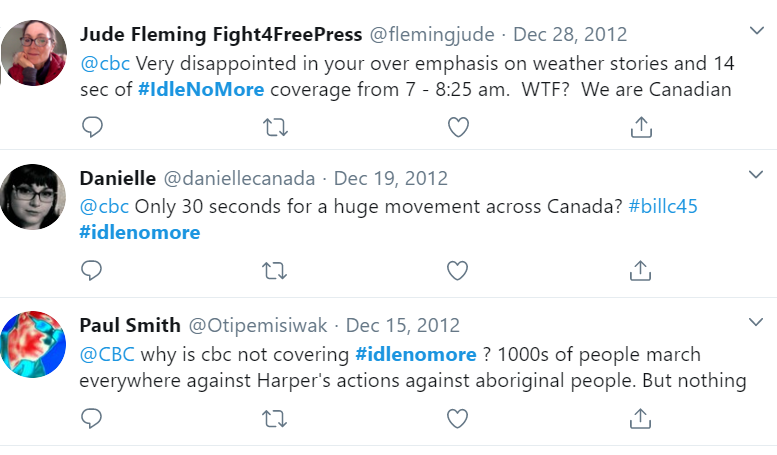

Early on #IDNM bwas ignored by mainstream media, much like an earlier movement Occupy Wall Street was originally ignored by media in the US.

“The early days, those first few weeks it was difficult to get anyone’s attention,” says King.

At the time #IDNM launched they found themselves in competition for media attention with a story about the “IKEA Monkey.”

Part of the #IDNM movement became pressuring mainstream media to pay attention. They focused on the public broadcaster, CBC.

CBC personalities like The National anchor Peter Mansbridge received a barrage of pushback on social media, some polite, some mocking and disparaging.

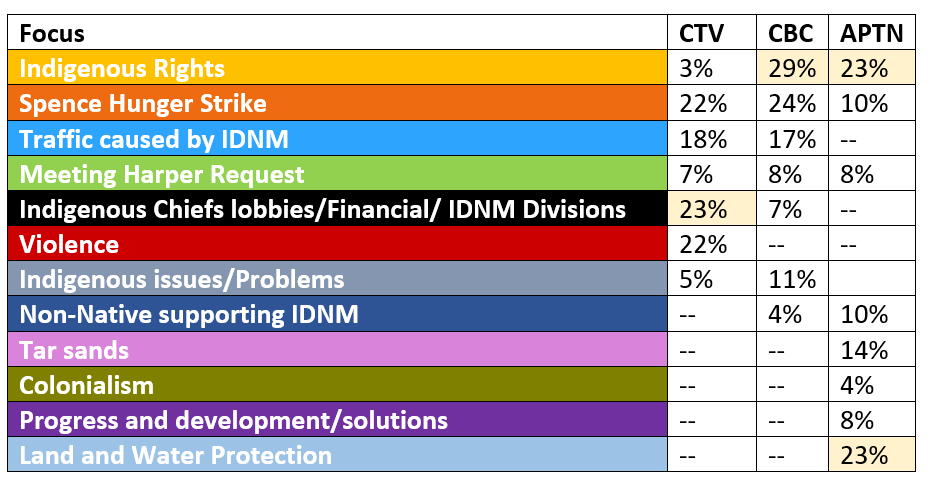

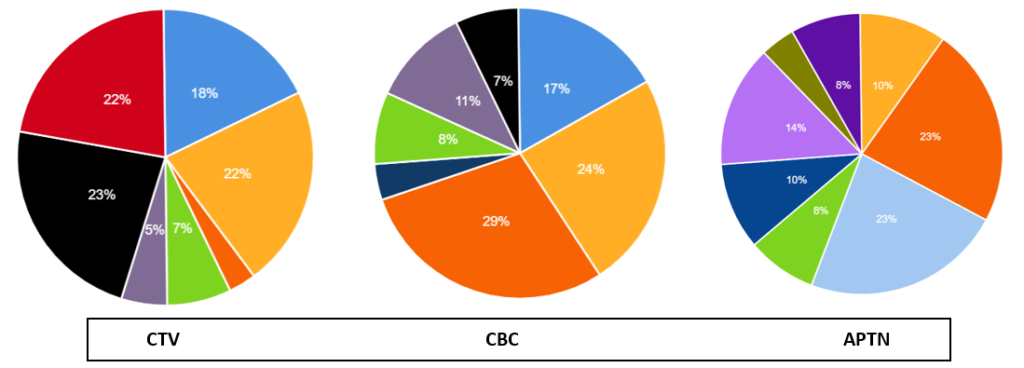

Professor Anna Mongibello, University of Naples, performed a content analysis of media in 2012 in her book Indigenous Peoples in Canadian News.She captured the coverage of #IDNM by three national news sources: APTN, the Indigenous broadcaster; CBC the public broadcaster and CTV a private broadcaster.

To APTN #IDNM was an Indigenous rights movement, with 23% percent of its coverage focused on that topic. APTN was the only media to define #IDNM as a movement about land and water protection (23%); and was the only media to mention tar sands (14%), progress and solutions (8%), or colonialism (4%).

To CBC the movement was primarily about Aboriginal Rights (29%), although this remained undefined, and a hunger strike (24%), which blocked traffic.

CTV the private broadcaster, but the highest rated of the three, was an outlier. The majority of its coverage focused on divisions in the movement (23%), and violence (22%); Neither APTN nor CBC understood the movement to be violent. CTV also focused slight more on traffic caused by #IDNM (18%) than CBC (17%); this topic was absent from APTN.

While it is not media’s job to be a spokesperson for a movement; media should be able to present the public an accurate idea of why #IDNM was happening. APTN coverage was closer to representing #IdleNoMore’s view of itself, and CBC was somewhere in the middle. It unlikely that viewers of CTV could have understood why #IDNM was happening. To Mongibello CTV’s focus on alleged violence and internal conflict served to undermine the legitimacy of the movement.

#IDNM was successful in pushing mainstream media to cover their issues, although it was not a portrayal that always accurately reflected the movement.

It was important then, if #IDNM was to be able to speak over mainstream media’s representation of it, and to communicate its message to Canadians that it post its own media, which it did in abundance on YouTube, Twitter and Facebook. It is unknowable if the efforts bore fruit. However, the knowledge, and effort of #IDNM to take control of its message can be considered a success in terms of social cohesion for the group.

Raising consciousness among Indigenous people

Organizers of #IDNM even years after the peak of the movement say that while there may not be dozens of weekly rallies, the movement has a lasting effect on Indigenous people.

“I think another significant change was the consciousness among Indigenous peoples was raised. I think that for the first time a lot of Indigenous peoples started contextualizing their own circumstances, started to understand why they were in the situation they were in,” says Hayden King.

“If nothing changes in terms of the government, and what they are doing we’ll always have to show resistance I feel that’s a real tragedy for Canada because instead of having the time and the opportunity to build ourselves and build our communities we’re always having to struggle and resist. On the other hand, that is what is building us into strong nations,” says Sylvia McAdam.

“Pride is the biggest thing, I see pride in in our youth especially and within our own grassroots people organizing and respecting each other and realizing there is much more we can do. We don’t have to rely on chiefs. We don’t have to rely on government. Our own organizing and that nation-hood building on the ground is important,” says Nina Wilson.

‘Flexing’

Nor has the #IDNM truly ended, it just changes form.

“What we are today is no longer Idle No More, but Idle No More lives in new movements,” says Hayden King. ” For me, and I’ve been involved in Indigenous activism for more than a decade now, I think of things as pre and post Idle No More. There was how we did politics before Idle No more and how we did politics after Idle No More and they are quite different.”

People involved in the movement were also certain that under the right circumstances the movement could arise again.

Although there have been other conflicts it was in January 2020 when a movement like #IDNM rose again.

January 2020 as sympathy protests were organized in support of a group of traditional chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en First Nation located in British Columbia.

The issue involves a long-standing dispute over whether or not the government has consent to built the Costal Gaslink pipeline through the unceded lands of the Wet’suwet’en protesters and their supporters were arrested along this road in early February, sparking solidarity protests and blockades across Canada.

While one hereditary chief supported the pipeline as did a number of elected chiefs, the traditional chiefs laid claim over a large swatch of traditional territory.

Wet’suwet’en who oppose the pipeline and their supporters were arrested along this road in early February, sparking solidarity protests and blockades across Canada.

One change was information in advance of actions was relayed by phone through small groups of volunteers instead of social media posts. Perhaps because of growing concern about police monitoring of Indigenous people. In the year following #IDNM it was revealed that police had scoured social media post and made a list of potential ‘radicals’ from participants in #IDNM.

The #IDNM hashtag resurfaced as marches and rallies took place. Along side however was the rise of a new hashtage and message: #ShutdownCanada which advocated for and achieved long term blockages of railway lines and other infrastructure.

The goal was to force the federal government, now a liberal minority government led by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to negotiate with the hereditary chiefs of Wet’suwet’en. Trudeau eventually agreed to do so, and an agreement is under negotiation.

However unlike #IDNM where the mood was somewhat optimistic, it did seem the new movement — and backlash against it – was more bitter, as mainstream media and social media became a battle ground debating Indigenous rights, and an outlet for frustration and in some cases racism.

“You do everything you can until you get to the point where you have to be active in a direct action… Until then we are completely invisible. Our issues aren’t covered, they aren’t considered important. Once we get to that point we get demonized, we get shown as violent and angry — like we are not willing to deal with things in a civilized way,” says Williamson.

1 reply on “Assignment 3: Case study #IDNM”

I deeply appreciate the chance I had to learn about a movement that was not widely covered in the US. I see many ways in which Idle No More reflects a new form of organizing that we’re seeing: highly decentralized with social media as a way of communicating between participants; a demand to be taken seriously and given attention by mainstream media; a relationship between online and real world actions. What was less clear to me was whether this was an offline movement that used social media well, or an example of an online community. It would be great to hear you explore a bit further the ways in which online spaces enabled connections and relationships that would have been unlikely to form offline, and thoughts on whether this movement was especially healthy in its online presence.